What I Learned from “Elephants in Your Mailbox”

Last updated 10/25/21 ✧ First posted 10/19/21

~16 minutes to read.

Contents

- 1 Suddenly, The Buck Stopped Here

- 2 Mail Order in the 1960s

- 3 Collecting Famous Names – and Experience

- 4 Horchow’s “25 Best Mistakes”

- 5 Parallels to Today’s Marketing

- 6 Trifles of Discerning Taste

- 7 Horchow’s “How-To Secrets”

- 8 The Crystal Ball Meets the Computer

- 9 Other Gems

- 10 What I Really Took From This Book

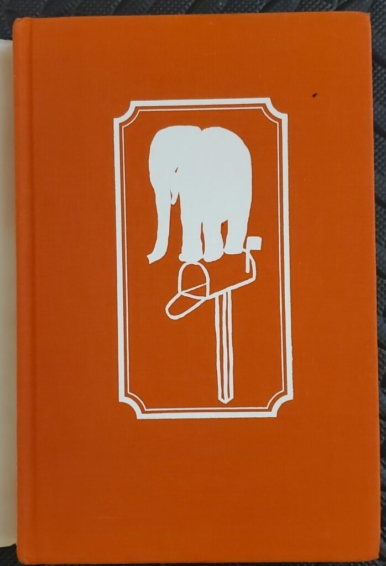

I read the book “Elephants in Your Mailbox: How I Learned the Secrets of Mail-Order Marketing Despite Having Made 25 Horrendous Mistakes” by Roger Horchow. It was fantastic!

Not only did I learn a lot about catalog marketing, which was more interesting than you may first think, I was also shocked at how so many aspects so closely mirrored today’s world of ecommerce. There are learnings and predictions here that can benefit a marketer today.

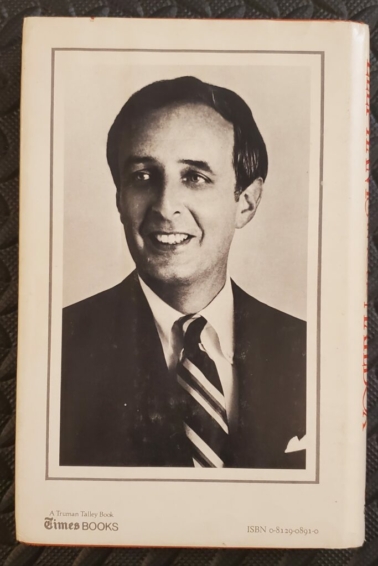

At 246 pages thick, it’s a solid read at a comfortable pace set by our accomplished yet humble guide to the world of catalog marketing, the CEO of the Horchow Collection himself. It was published in 1980 by Truman Talley Books.

Here are the links to it on Goodreads and Amazon.

Since the publish date is nearly a half-century ago, there are some differences in era that show through. But the language still reads perfectly today, it’s smooth and witty and casual and smart.

Horchow packed a ton of education and history in here, but is not snooty or arrogant about his role. In fact, his emphasis on his mistakes and flaws still make him seem like the underdog, and you get a sense of who he was. It was a very personal read.

Horchow was employed by Neiman Marcus for a while, then went elsewhere (to the Kenton Company) and bought out the burgeoning catalog division he was running, and turned it into his own Horchow Collection.

Years after this book was published, he sold it for a very tidy profit back to his old employers Neiman Marcus.

Suddenly, The Buck Stopped Here

The book opens on Horchow’s first day in his business after buying it out completely in his name. You can feel the nerves in his writing as the realization, and the responsibility, really set in. He could no longer defer to any abstract “theys” and “thems” of his old employers:

“From now on, ‘they’ and ‘them’ were spelled H-O-R-C-H-O-W.”

The company had lost a million dollars per year in the last two years it had been in business, and he had just spent a million bucks of his own money (and his friends’ and family’s) to buy the joint.

I’d be nervous too.

He dials back to his childhood and mentions how his mother was a concert pianist who owned a beautiful Steinway grand piano, and he’d hear the songs of George Gershwin float through the house. Remember that – that’ll come up at the end.

Mail Order in the 1960s

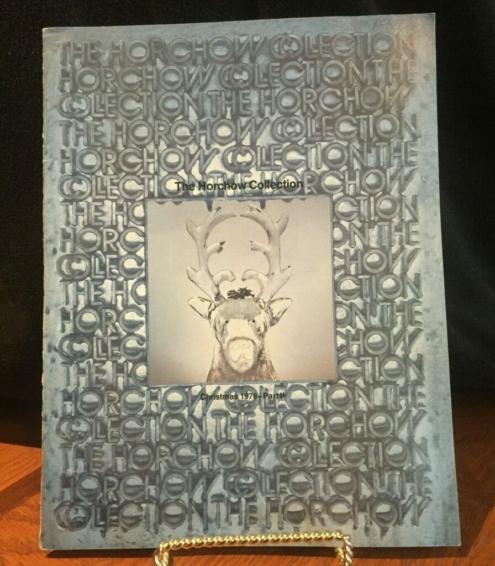

Direct mail marketing in the US during the 60s was absolutely the black sheep of ad channels. Major retailers, such as Neiman Marcus, used catalogs as an afterthought to an afterthought, just to take care of their extra inventory. It wasn’t seen as a serious line of business.

There were no independent catalogs. Every catalog was an extension of a brick and mortar location. It simply wasn’t done otherwise, and was barely paid attention to by these locations.

Horchow was interested in the idea of catalogs from an early age, so when he was put in charge of various catalog marketing departments at different retailers, he had a wider vision for them than the owners of those companies did.

After bouncing around for a while, he left Neiman Marcus and went to the Kenton Collection, where he told them they should expect to lose a million dollars the first year, maybe break even the second year, and then start making millions – god willing!

Things went about how he predicted; he made a lot of mistakes, but had a lot of skill and a fair amount of luck. But the Kenton Company simply wasn’t interested in this tertiary channel, so when Horchow offered them a million, they took it. (This would be about $6.5 million in 2021 dollars.)

By the next year, the Horchow Collection was already beginning to make its millions.

Collecting Famous Names – and Experience

Horchow was surprised and delighted by how many celebrities he’d find in his order list – and how many of them would call in. In fact, the homey nature of the catalogs and copy made many customers have beliefs about the character of the company. They did a great job maintaining a “down home Texan with good taste” brand image, and would get many shoppers writing in like old friends.

Although he had a staff of select buyers, everyone had advice on what they should sell – and they considered products from any source. One of his daughters found a head scarf in Mexico that sold in the hundreds of thousands.

One of the biggest takeaways was as simple as “customers buy things they can use” – it sounds obvious, until he looked at his competition and realized many things being sold just weren’t useful to anyone.

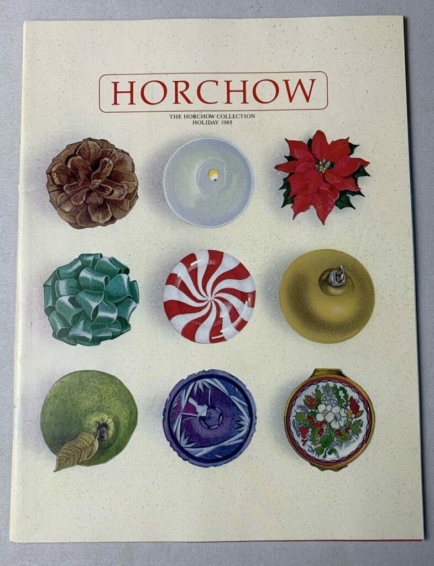

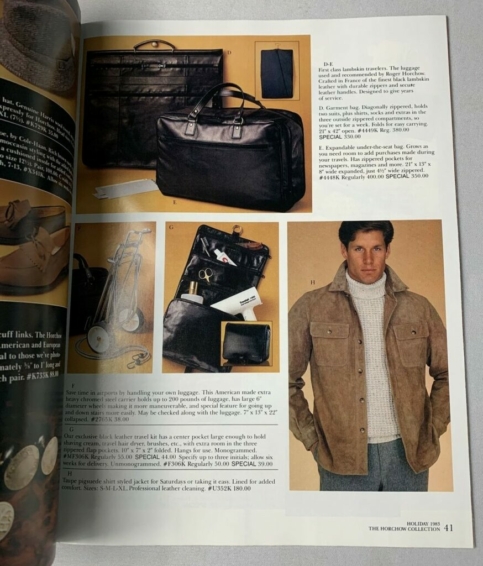

The mix of the catalogs changed year to year – sometimes lots of apparel, sometimes lots more home goods. Repeat items were common and were put in the “Horchow Classics” section – since who knows if it’s someone’s tenth catalog or their first? Reliable sellers were still analyzed before every catalog went out.

The best fashions were clothing that could easily fit multiple sizes; Horchow never tried to be fashion first, and never thought of himself as a style leader, but would look for the best of the current trends and make sure he got it right.

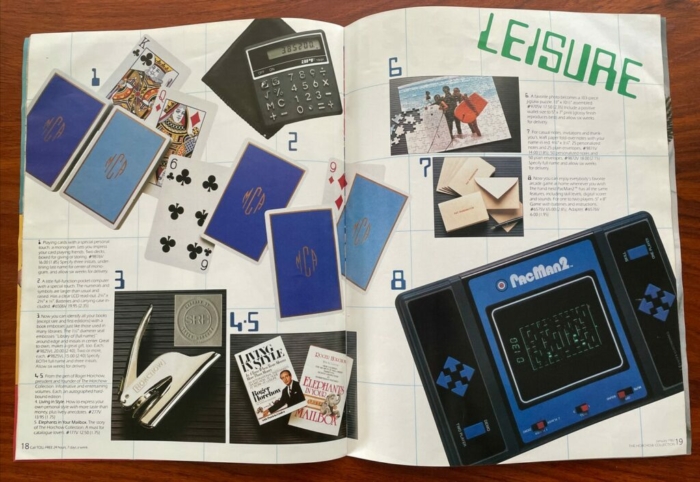

In many parts of the book, Horchow talks about marketing personas without naming the concept exactly. He never used the word “segmenting,” but began to use it extensively, especially with the advent of computers being able to sort through mailing lists.

Indeed, the mailing list management was a major issue, and quite a big trade “secret sauce.” Some companies shared lists of address, and other companies were address list brokers, a much less sophisticated version of what exists today.

These companies would only rent the lists for a certain amount of uses. They enforced this by including some fake names on the list, and if they found you were still mailing to those names after your agreement was up, the whole address list community would blacklist you.

Oh, but speaking of famous names, I was shocked to see this photo in the middle section of a catalog photo that includes two child models – Luke and Owen Wilson.

Yes, that’s Luke Wilson and Owen Wilson, the now-famous actors, as little kids playing “Texas wheeler-dealers.” I wonder if they remember this.

Horchow mentions that the real “rent payers” were just ten customers who were spending over $10k/yr with them. ($10k/yr in 1965 dollars is about $90k/yr in 2021 dollars – wow! Talk about the Pareto principle in action.)

Horchow kept high standards for the catalog, and after a few years, designers were beating down the path to his door just to get featured in the catalog. Of course, lots of copycat catalogs also popped up, although none lasted more than a few years.

In one case, a porcelain pansy ring was featured in the catalog with no price or copy by mistake. They sold $8,000 worth despite some people not even knowing what it was. They later ran the product again with price and copy, and sold less.

Horchow’s “25 Best Mistakes”

- Always look for the worst possibilities first.

- Take your markdowns as soon as possible – in merchandise and in people.

- Don’t deal with the same sources all the time, whether banks, printers, photographers, art directors, paper mills, box manufacturers, or designers. It makes them feel too secure, and pretty soon your business is taken for granted and someone else is treated better.

- Don’t be too dependent on one source for any one project.

- Don’t think declines in the economy will not affect your business. Heed the signs at the earliest moment.

- Don’t experiment until you have set aside the amount of money you plan to lose. Budget in advance of the experiment, not as it is going on.

- Don’t hire friends, don’t buy from friends, don’t borrow money from friends. (Horchow broke this rule a few times and lived to regret it.)

- Don’t worry too much about competition; mind your own business.

- Don’t start with quantity, start with quality – in merchandise and in employees. Pick people you think you can spend long periods of time with.

- Don’t expand for greatness until greatness comes near.

- Don’t listen to outsiders who want either to do you a favor or “save you money.”

- Don’t accept internal recommendations without making sure you understand all the internal relationships.

- Don’t involve yourself, as boss, in intracompany gossip; keep aware but keep aloof.

- Don’t let the Suggestion Box be just for complaints.

- Don’t think your personal objectives will stay the same.

- Don’t waste time with schemers – and the more serious the scheme, the more the loss.

- Don’t buy something “about to be made.”

- Don’t send employees on buying trips until you see concrete evidence of their ideas of quality and taste.

- Don’t try to outguess the credit manager.

- Don’t forget: factories burn down, warehouses flood, molds break, shipments are stolen, makers break legs, and presidents die; insurmountable catastrophes are insurmountable.

- Don’t believe your own press clippings.

- Don’t allow success to lower your standards.

- Don’t forget: more people, more problems.

- Don’t assume people are honest. A security system protects the honest as much as it uncovers the dishonest.

- Don’t assume people are dishonest; it destroys good working conditions.

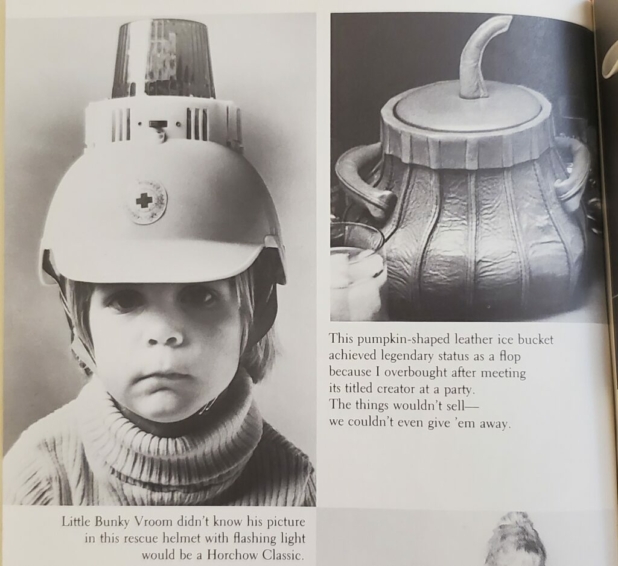

Horchow also goes in detail on various products he thought would be winners but were instead total stinkers – certain chests or pumpkin-shaped bowls, or a lot of things endorsed by celebrities or royalty – which no customer actually cared about when there were other similar products out there for cheaper.

The company had a “Fruitcake Award” for the worst item of the year, just internally of course, which every buyer ‘won’ at some point or another. They also categorized items as “hummers” or “bummers” which tells me that in the 1970s, “hummer” was not yet slang for a sexual act. Sort of an awkward-by-accident chapter there.

Parallels to Today’s Marketing

One parallel to modern times that I found fun was their process of “making it as easy as possible to order.” Horchow received complaints that the order form was too complicated, so he reduced form fields and made it easier to write in. We’re doing the same thing on websites today!

Of course, back then the rules were wide open – customers could simply rip out a page of a catalog, circle an item, and write “3” next to it, and that’s all they had to do to order three of it. Much harder to do on a website.

One thing Horchow talks extensively on is customer service. With some slight updates to the technology mentioned, you could basically lift these passages and put them in a great business book today.

The same kind of angry and confused customers that Amazon and other ecommerce stores get now still existed back then, and they had an extensive department to deal with them, and please them further:

Today, when a Horchow customer is unhappy or dissatisfied, we don’t just try to make things right, we strive. And the very last question we ask is: “Are you still going to be our customer?” If the answer isn’t, “Yes,” we don’t stop.

There were also people who returned clothes after a month (obviously worn) who would soon find themselves cut off, but other than the obvious scammers, Horchow had a surprisingly generous and modern return policy.

One of the biggest parallels is the talk of the US postal service. So much of the business depends on delivery people, and if there are delays there, it can reflect badly on Horchow by accident. The same bottlenecks he dealt with are still being dealt with by Amazon and other retailers today – in many ways, worse.

Trifles of Discerning Taste

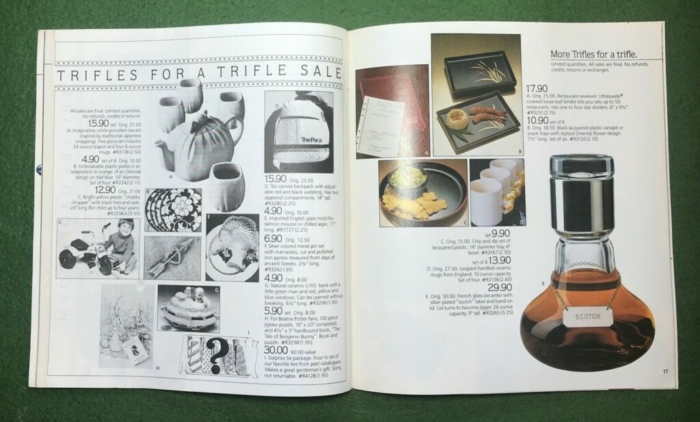

In 1977, Horchow launched a complementary catalog called Trifles, featuring more luxurious items designed around a certain family. This idea really stuck with me.

The whole inspiration came from seeing a model in an elegant setting, looking especially regal. They decided to build around her, creating a fake couple named G. G. Westfall and her husband Michael Bradford Westfall, Jr. Their children, Brad III and Missy, the dog Muffie, the cat Charlie, the whole extended community, the products all emblazoned with GGW and MBW monograms, the whole nine yards.

This is fascinating idea to me, and is maybe comparable as to what Acura is to Honda (for example) – just a lot more specific, with stories and lore behind it.

This makes me want to invent my own set of rich, stylish, successful personas just to model my own life after what they’d be doing. They’d probably know better than me.

Horchow’s “How-To Secrets”

How do we find your merchandise?

Basically, anywhere and everywhere – friends, family, buyers, traveling, designers coming to you – the sky is the limit.

When buying products to stock in the catalog, Horchow always asks himself, “who would I buy this for?” If he couldn’t think of someone specific in his life, he didn’t stock it. Every item had to pass the test of, “would someone I actually know, actually want this as a present?”

How do we evaluate the merchandise?

- Is it a good value?

- Will it give us enough profit?

- Is it a straightforward, honest item?

- Is it of good quality?

- Is it easy to pack and ship? (Can it be made to fit?)

- Is there a lot of competition on the item?

- Will it be understood from a photograph? (Stationery is one example that does not sell well from photographs.)

- Is it a sensible item, or would it be used just to create a sensational image?

- Have we had anything like it before to which we may compare sales potential?

- If not, is it worth trying?

- Will it be exclusive to the Horchow Collection?

- Is it important to us that it be exclusive?

- If it is not exclusive, where else will it be sold?

- How long will we be allowed to have the item before it is sold to the general market?

- If it is clothing, will there be a size problem, or will one size fit all?

- Can we explain how it fits, or works, in our copy or over the telephone? (We can’t simply say, “oh, you’ll just have to try it and see.”

What about our suppliers?

- Is the supplier reliable?

- Will we be able to get reorders?

- Have we had previous experience with the supplier?

- Will the item being offered sell a minimum of, say, ~$7,000 or more at retail? (pending inflation)

- If we don’t sell all we buy, would the supplier allow us to return unsold goods?

Indeed, one major issue is inventory. It sucks to be left with most of the item you bought. It also sucks to find a supplier who handmakes an item, order all 20 of their stock, and have it be so popular that you call them back and ask them for 2,000 more – you’ll likely be told it would break them, so you have to deal with the customer fallout. Horchow spends a lot of time on inventory issues.

Horchow also goes in detail on other secrets that I don’t find relevant enough to reproduce here, like his methodology on profitability, and why you might choose one item over another one specifically.

The Crystal Ball Meets the Computer

Near the end of the book, Horchow talks about the state of catalogs as they were in the last 70s: increasingly competitive, harder and harder to drive a profit from, as we see today with many forms of marketing. He offered his predictions on the future.

At some point we will have television presentation of goods, via cable, perhaps, where a beautiful woman or handsome man will model, or will describe items, offering them one at a time while you sit in your living room or bedroom and punch a push-button phone or some other kind of registering device which will order what you want in color, size, and numbers you desire.

Everything will be automatic, including a credit check, and, after a period of time in which you will be allowed to change the data – or change your mind – your order will begin moving to you in something like five or ten seconds after you push the final selector.

Essentially, Horchow is predicting QVC and phone ordering. He goes on to say more about phones:

One facet of electronic ordering we have been waiting for since the early 1950s is the television telephone. Here, again, the advantage would be primarily in speeding up ordering and credit checks.

I anticipate the use of credit cards will be enhanced in a short time. We’ve been waiting for video telephones for more than a quarter century, but a credit-card verification system should easily beat that timetable.

With it you may insert your card, possibly punching a secret code number on your telephone, and have your order entered into the computer in a matter of seconds.

With the advancement of this concept, you will ultimately place an order directly to a computer which will be able to talk to you.

Not bad. Not bad at all!

Horchow predicts that customers will value the convenience of shopping and ordering at home more and more, especially as more people work, and it will become a habit, a way of life.

He also predicts that the biggest bottleneck will continue to be the delivery systems – like the postal service or FedEx. So, in a way, he goes on to predict something like Amazon’s drone delivery:

Off in the future we may see a new kind of transportation system which will enable the transmission of goods almost instantly. … Who’s to say that rocket shipping is another century away?

Safe to say, I think he nailed it on all counts.

Other Gems

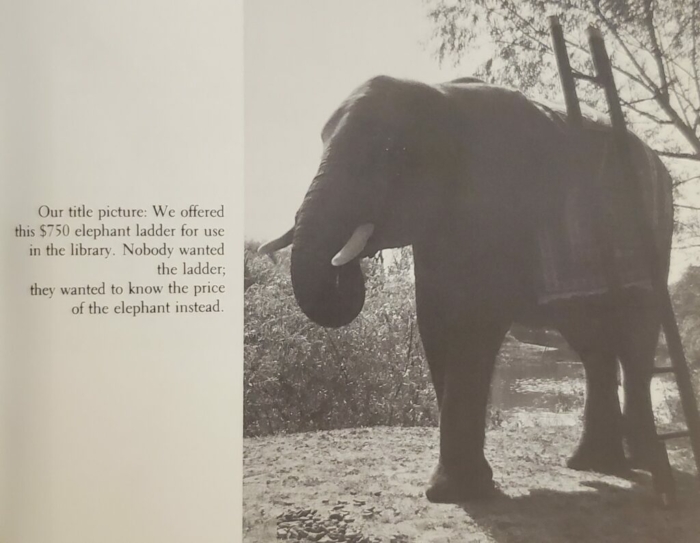

When I first opened the book, I assumed the titular “elephants in your mailbox” meant the catalogs themselves. But the phrase has a funnier origin:

Once we offered an exotic elephant ladder (used to mount the huge beasts) and had a genuine elephant in the catalogue illustration. We didn’t have grand sales results on the ladder, but we got several inquiries about the elephant: Why hadn’t we included its price?

A tongue-in-cheek letter writer said he knew why we didn’t offer elephants for sale: “The problem is supply.”

Our Customer Service director, getting in the spirit of things, replied, “The problem isn’t supply. India’s full of ’em. The problem is getting the elephants in your mailbox.”

And while I’ve never given it much thought, this was the time that credit cards were catching on in the mainstream US population. Horchow found himself at the right place at the right time to take advantage of the ease of ordering this allowed people, and quickly expanded his phone business. Hard to believe they started with one single phone line, on regular business hours only.

To get rid of inventory that wasn’t selling in catalogs, they eventually opened up a small number of stores called Horchow Finales, which were major hits – sort of like an overstock/outlet dealer today. Funny how they reversed the “retailer adds on a catalog” practice from the 60s. And also funny how that parallels what Amazon is doing opening physical stores today.

What I Really Took From This Book

Honestly, this book had a lot more gems, and I’m finding it hard to get them down on this blog. I think I may have gotten about 50% of the best information here, and only 5% of the personality. I really did enjoy this book and felt like I’d gladly get a drink with Horchow by the end of it.

Although the Horchow Collection exists as a website today, there is sadly no mention of Roger Horchow or any of this fascinating history. It’s just another site. I always hate this. This is a place with an interesting and storied history dating back over 50 years, and yet they make no effort to differentiate themselves with it, letting themselves appear no different than some no-name affiliate marketer with a decent sense of style.

I mean what’s the point of the Horchow name if you’re not going to leverage the brand? Ridiculous.

But remember how I told you to remember how Gershwin music floated through Horchow’s childhood house? Years after this book was published, when he sold the Collection to Neiman Marcus for quite a lot of money in 1988, he went back to his passions.

In 1992 he became a Broadway producer with Gershwin’s Crazy For You, and went on to live the rest of his life as a successful producer of all kinds of musicals. The mail order catalog business, which engrossed him for decades, and which engrossed me in this book, is nothing more than a sentence or two on his Wikipedia page.

Not to be all sappy here, but finding this out after finishing the book brought a tear to my eye. It’s so easy to just get lost in business forever, but all these things that we think matter so much, really don’t at the end of the day. Imagine if he’d said “well, I’m so good at this business, I’m going to keep on doing it for another 30 years.” Some men in advertising do that, and I don’t envy it.

So the biggest thing I learned from this book wasn’t in the book at all, but rather how much more than a collection of great marketing ideas a person can be.

Roger Horchow passed on May 2nd, 2020. I was a little sad I didn’t get to send him an email saying I liked his book. But I would recommend it as a delightful detour to you, with the occasional insight that still rings true across channels today.

✧ ✧ ✧

Written by Ethan J. Hulbert.